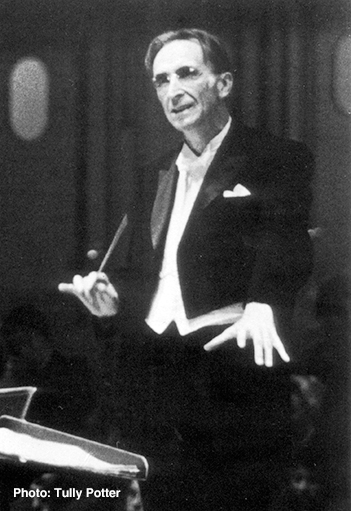

Hans Rosbaud

Hans Rosbaud received his first music lessons from his mother, who was an accomplished musician. His academic education was founded upon classical languages and culture, but he also learnt to play several string and wind instruments, entering the Hoch Conservatory in Frankfurt, where his teachers included Bernhard Sekles for composition and Alfred Hoehn for piano. He also studied conducting and began his professional career in 1921 at Mainz, having been selected from a wide field as the director of the newly-formed municipal school of music, which soon developed a strong reputation throughout Germany; he also conducted some of the municipal symphony concerts in the city. Rosbaud was appointed chief conductor at Radio Frankfurt in 1929. Major contemporary composers were regular participants in the station’s concerts and among the first performances which Rosbaud conducted were those of Bartók’s Piano Concerto No. 2 (with the composer as soloist), Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms, Hindemith’s Concert Music for Brass and Strings and Schoenberg’s Variations Op. 31.

The establishment of the Nazi government resulted in Rosbaud coming under increasing political pressure, and in 1937 he left Frankfurt to become chief conductor at Münster, where his responsibilities included opera as well as symphonic performances. Four years later he took up a similar position in Strasbourg, which had been annexed by Germany. Here once again Rosbaud developed a flourishing musical life, despite numerous obstacles being placed in his way by the political authorities; and his persistent efforts on behalf of members of his orchestra who suffered persecution by the authorities won him the respect and support of the population. Following the end of World War II he was appointed chief conductor of the Munich Radio Orchestra and of the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra by the American military authorities, who gave him considerable support in his work of rebuilding musical life in the devastated city. He was the first conductor from Germany to be invited to appear in France after the war, and was warmly received. He left Munich in 1948 to take up the position of chief conductor of the South West German Radio Orchestra, Baden-Baden, where he was based for the rest of his life.

A prime mover in the establishment of the Aix-en-Provence Festival from 1948 onwards, Rosbaud appeared there annually until 1959. He added to his responsibilities in 1950 when he became conductor of the Zürich Tonhalle Orchestra and at the Zürich Opera, assuming the role of chief conductor of the Tonhalle in 1957. His successes at Baden-Baden and at the neighbouring Donaueschingen Festival of Contemporary Music, following its resumption in 1950, led to his international recognition. During the 1950s he became especially noted for his performances of the music of Schoenberg: at only eight days’ notice, he took over from Hans Schmidt-Isserstedt as the conductor of the first performance (which was recorded) of Schoenberg’s opera Moses und Aron in 1954 in Hamburg and he conducted the work’s stage première at Zürich in 1957. Rosbaud’s fame was reflected in his activity as a guest conductor of the major European orchestras and in his concert tours abroad, notably to South America, South Africa and the United States. He made a particularly strong impression with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and was seriously considered as a successor to Fritz Reiner, a move that was prevented by his untimely death in 1962.

Rosbaud was an undemonstrative conductor. Bernard Haitink has recalled that ‘…as he approached the podium you thought, surely that can’t be the conductor’, yet he achieved excellent results. As the Chicago-based critic Robert C. Marsh commented in a review of Rosbaud’s first concert with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in January 1959, ‘This modest, self-effacing conductor has authority, an ear for color and a sense of style. He is a musician to hear rather than watch... He seems to have the most naive idea of showmanship, but his musicianship cannot be questioned.’ The esteem in which he was held by his contemporaries was illustrated by the composer Francis Poulenc’s comment, quoted in Paris-Match in November 1954, that ‘The taste of music buffs little resembles that of professional musicians. Music buffs believe that the greatest living conductor is Toscanini; musicians know that it is Hans Rosbaud.’ And another major French composer, Pierre Boulez, regards Rosbaud as a model of what a conductor should be.

His success as a trail-blazer in the performance of contemporary music, and the numerous resulting recordings which he made, overshadowed to a certain extent the recognition of Rosbaud’s great skills as an interpreter of the traditional repertory. Here his commercial recordings are fewer, although fortunately many of the numerous radio recordings which he made, predominantly for South West German Radio, have been released. He was an excellent conductor of Sibelius, where his lean and forensic conducting style perfectly suited the brooding atmosphere of this composer’s music. This stripped-back approach to performance also resulted in stylish performances of the music of the Classical and early Romantic era, such as the symphonies of Haydn and the piano concertos of Mozart and Beethoven. His readings of the symphonies of Mahler and Bruckner stand at the opposite pole to the intense style adopted by other contemporary conductors, but the power of the music remains. Rosbaud’s performances from Aix of several of the Mozart operas were commercially recorded and remain models of style, as does his account of the tenor version of Gluck’s Orphée et Euridice with Léopold Simoneau in the title role. A man of wide learning and interests, Rosbaud included the study of nuclear physics among his hobbies.

© Naxos Rights International Ltd. — David Patmore (A–Z of Conductors, Naxos 8.558087–90).